Extreme heat is an urgent and growing threat to human health, exacerbated by the escalating effects of climate change.

Rising global temperatures have led to an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme heat and heatwaves, which pose significant risks to individuals and communities.

Prolonged exposure to extreme heat can lead to a range of health issues, including heatstroke, dehydration, respiratory problems, and exacerbation of existing conditions.

Vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, children, and those with preexisting health concerns, are particularly at risk.

In 2023 alone, infants and adults over 65 experienced over 13 billion days exposed to heatwaves, an increase of over 20% compared to 2022. On average, each infant faced over 8 extra days of intense heat, while older adults experienced an additional 9 days compared to levels from 1986–2005. Source 2024 Report of the Lancet Countdown

Heat-related health impacts are also reflected in mortality rates. Between 1990–99 and 2014–23, heat-related deaths among adults over 65 have more than doubled, underscoring the growing toll of extreme heat on vulnerable populations. Source 2024 Report of the Lancet Countdown

The impacts extend beyond health to daily life. In 2023, heat stress reached record highs, resulting in lost sleep, restricted physical activity, and a staggering $835 billion in lost labor productivity worldwide. Source 2024 Report of the Lancet Countdown

Developing countries face the heaviest burden, amplifying global inequalities as they struggle with both health and economic losses tied to climate change. Source 2024 Report of the Lancet Countdown

The good news is that every heat death is preventable. Saving lives demands immediate action in the form of early warning systems, multi-sectoral public policy, public health initiatives, infrastructure improvements, and mitigation of climate change to safeguard human lives.

Sensitivity

Some populations are more vulnerable than others to physiological stress, exacerbated illness, and an increased risk of death from exposure to hot weather.

Especially vulnerable populations include those over 65 years of age – particularly those with chronic medical conditions, infants and children, pregnant women, outdoor workers, athletes and attendees of outdoor events (e.g. music festivals), and the poor.

Gender can also play an important role in determining heat exposure.

Why are some people more vulnerable than others?

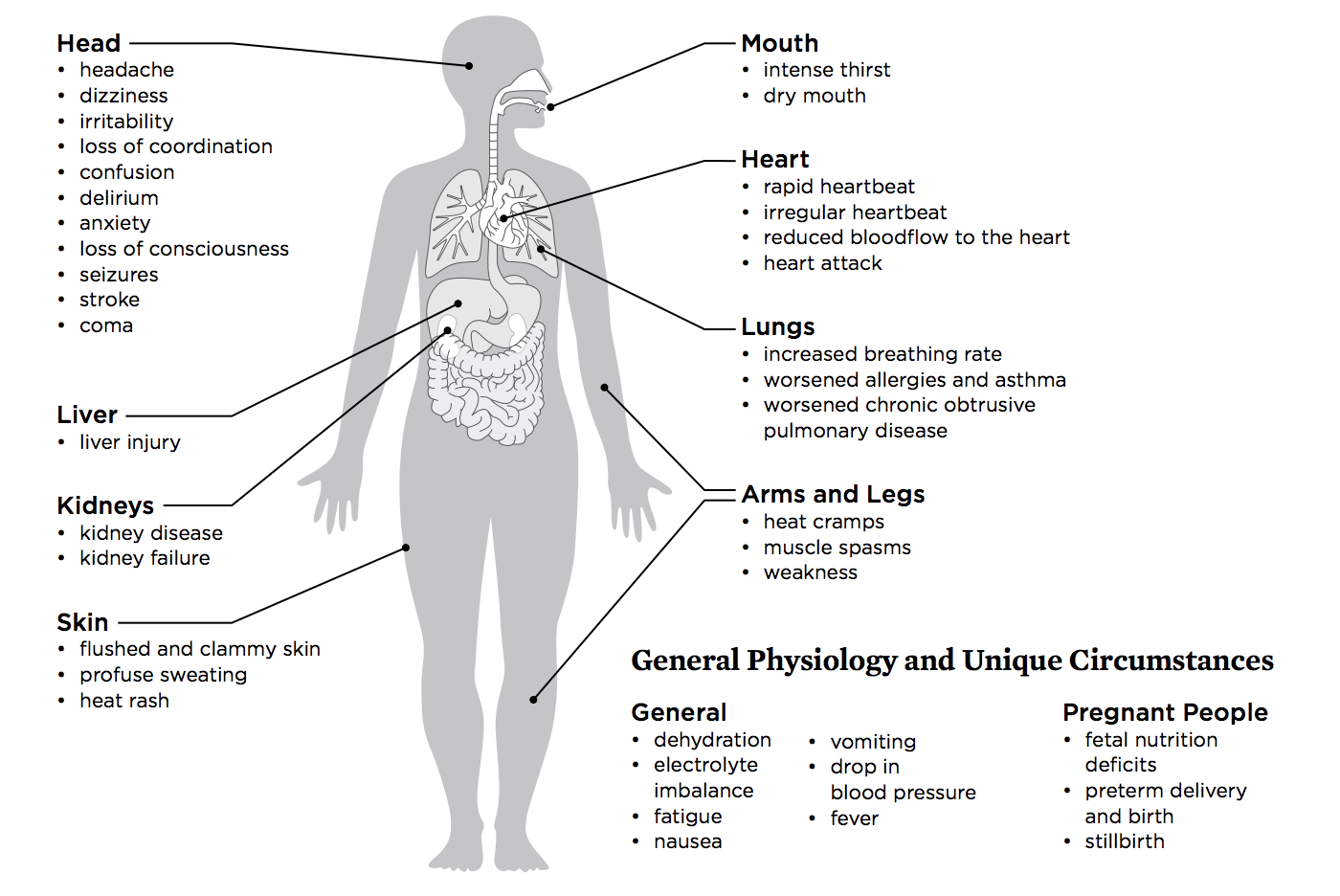

How Does Heat Affect Health?

Rapid rise in heat gain due to exposure to hotter-than-average conditions compromises the body’s ability to regulate temperature, and can result in a cascade of illnesses including heat cramps, heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and hyperthermia. Even small changes from seasonal average temperatures are associated with increased illness and death.

Deaths and hospitalizations from heat can be rapid or delayed, and can result in accelerated death or exacerbated illness in the already frail – especially during the first days of a heatwave. Temperature extremes can also worsen chronic conditions, including cardiovascular, respiratory, and cerebrovascular disease and diabetes-related conditions.

Heat also has important indirect health effects. Heat conditions can alter human behaviour, the transmission of diseases, health service delivery, air quality, and critical social infrastructure such as energy, transport, and water. Heat influences brain functioning and behaviour, and people with mental health issues and/or prescribed medications which limit the body’s natural cooling functions are especially vulnerable.

The scale and nature of the health impacts of heat depend on the timing, intensity and duration of a temperature event, the level of acclimatization, and the adaptability of the local population, infrastructure and institutions to the prevailing climate. The precise threshold at which temperature represents a hazardous condition varies by region, other factors such as humidity and wind, local levels of human acclimatization and preparedness for heat conditions.

How Heat Affects Our Bodies

Source: Killer Heat in the United States, UCS, 2019, p.9

Organs Damaged by Heat Exposure

Organs Mechanisms

Ischemia (limited blood flow) Heat Cytotoxicity (cell toxicity) Inflammatory Response Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation Rhabdomyolysis (muscle tissue breakdown)

Brain

Heart

Intestines

Kidneys

Liver

Lungs

Pancreas

| Organs | Mechanisms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemia (limited blood flow) | Heat Cytotoxicity (cell toxicity) | Inflammatory Response | Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation | Rhabdomyolysis (muscle tissue breakdown) | |

| Brain | |||||

| Heart | |||||

| Intestines | |||||

| Kidneys | |||||

| Liver | |||||

| Lungs | |||||

| Pancreas |

How Does Heat Affect Health Systems?

Hot weather, alone or in combination with other natural disasters, has the potential to cause wide-scale health emergencies, exacerbate risks of mass gatherings (such as music concerts, religious or sporting events), and disrupt emergency health services.

Periods of high temperatures have the potential to increase the patient burden on emergency health services, increase demand on ambulatory services, and increase emergency admission and hospitalization. Increasing temperatures also mean increased costs for health facilities to provide sufficient cooling and to retrofit health facilities to improve ventilation, cooling, insulation, energy and water resources to function efficiently.

Hot weather also increases heat stress for health workers. To prevent heat strain in health workers, sufficient rest and cooling times, safety while wearing personal protective equipment, and other measures are needed. Tool tip Learn more on how to protect health facility staff from heat strain and heat-related illness, and how health workers and other responders can manage heat stress while wearing personal protective equipment (PPE).

Monitoring and Measuring Impacts of Heat on Health

There are a range of indicators available to help governments monitor and measure the impact that high temperatures have on public health. Below are common indicators used to measure the impact of health and wellbeing. Tool tip Learn more about network priorities for Vulnerability Science (Pillar 2).

Indicators for Monitoring and Measuring Impacts of Heat on Health

Metric Good Practice Indicators Examples

Excess all-cause mortality

- Estimated daily excess all-cause mortality by age group and region (1-64)(Over 65)

- All-cause mortality, all ages and by ages

UK Heatwave Mortality Monitor

European Monitoring of Excess Mortality

Pascal et al. 2021. Evolving heat waves characteristics challenge heat warning systems and prevention plans. International Journal of Biometeorology volume 65.

Heat-related mortality

- Number of summertime heat-related deaths by year;

- Annual rate for deaths classified by medical professionals as “heat-related” based on death certificate record

US-CDC Environmental Public Health Tracking

US EPA Climate Change Indicators: Heat-Related Deaths

Heat-related illnesses

- Hospitalization rates for “heat-related” illnesses such as heat exhaustion, heat cramps, mild heat edema (swelling in the legs and hands), heat syncope (fainting), and heat stroke, based on hospital discharge records for patients who are admitted to the hospital for 23 hours or more;

- Age-adjusted rate of hospitalization for heat stress per 100,000 population;

- Crude rate of hospitalization for heat stress per 100,000 population;

- Number of hospitalizations for heat stress;

- Heat Stress Emergency Department Visits

- Emergency consultations by general practitioners for heat stroke or dehydration, all ages and by age, as a primary or second cause of diagnosis

US EPA Climate Change Indicators: Heat-Related Illnesses

US-CDC Environmental Public Health Tracking

US-CDC Heat Stress Illness Indicators

Pascal et al. 2021. Evolving heat waves characteristics challenge heat warning systems and prevention plans. International Journal of Biometeorology volume 65.

Emergency department visits for heat stress

- Annual age-adjusted rate of emergency department visits for heat stress per 100,000 population;

- Annual crude rate of emergency department visits for heat stress per 100,000 population;

- Annual number of emergency department visits for heat stress.

- Emergency room visits for hyperthermia, dehydration or hyponatremia, all ages and by age as a primary or second cause of diagnosis

US-CDC – Environmental Public Health Tracking

US-CDC Indicators and Data

NIHHIS Experimental Heat Health Monitor

Pascal et al. 2021. Evolving heat waves characteristics challenge heat warning systems and prevention plans. International Journal of Biometeorology volume 65.

Energy demand

- Heating and cooling degree days

US-EPA Climate Change Indicators

Productivity loss

- Working hours lost to heat stress;

- Percentage of GDP lost to heat stress

Working on a warmer planet: The impact of heat stress on labour productivity and decent work (ILO)

Exposure measures

- Number of Extreme Heat Days;

- Dates of Extreme Heat Days;

- Number of Extreme Heat Events;

- Dates of Extreme Heat Events

US CDC Indicator: Historical Extreme Heat Days and Events

Temperature distribution

- Daily estimates of maximum temperature for summer months (May-September);

- Daily estimates of maximum heat index for summer months (May-September)

US-CDC Indicator: Temperature Distribution

| Metric | Good Practice Indicators | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Excess all-cause mortality |

| UK Heatwave Mortality Monitor European Monitoring of Excess Mortality Pascal et al. 2021. Evolving heat waves characteristics challenge heat warning systems and prevention plans. International Journal of Biometeorology volume 65. |

| Heat-related mortality |

| US-CDC Environmental Public Health Tracking US EPA Climate Change Indicators: Heat-Related Deaths |

| Heat-related illnesses |

| US EPA Climate Change Indicators: Heat-Related Illnesses US-CDC Environmental Public Health Tracking US-CDC Heat Stress Illness Indicators Pascal et al. 2021. Evolving heat waves characteristics challenge heat warning systems and prevention plans. International Journal of Biometeorology volume 65. |

| Emergency department visits for heat stress |

| US-CDC – Environmental Public Health Tracking US-CDC Indicators and Data NIHHIS Experimental Heat Health Monitor Pascal et al. 2021. Evolving heat waves characteristics challenge heat warning systems and prevention plans. International Journal of Biometeorology volume 65. |

| Energy demand |

| US-EPA Climate Change Indicators |

| Productivity loss |

| Working on a warmer planet: The impact of heat stress on labour productivity and decent work (ILO) |

| Exposure measures |

| US CDC Indicator: Historical Extreme Heat Days and Events |

| Temperature distribution |

| US-CDC Indicator: Temperature Distribution |

Key Resources

Guidance (ES)

Secretaría de Salud, Gobierno de México

2020

Technical Report

Guidance

Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC)

2017

Case Study

Hermosillo, Mexico, Captures Heat-Related Illnesses at Medical Facilities Using New Database

Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC)