Life Without Power Spells Daily Misery for Yangon’s Residents

Published: January 29, 2025

Burma

This article was originally published by The Irrawaddy

Dealing with the sticky heat amid Yangon’s chronic power outages has become the New Normal for Phyo Htet in Bahan Township.

Phyo Htet teaches science classes online, most of the time without electricity from the national grid. Instead she uses other power sources—a power bank or diesel generator. Only well-off households can afford solar power as the panels are expensive.

Even longer and more frequent blackouts since January add to the burden of daily life for Myanmar’s urban residents, especially in Yangon’s residential buildings.

Anything that requires electricity—from cooking and pumping up water to charging electronic devices for work or study—has to be done in the brief intervals when the power is on, day or night.

“When there is no power, there is no water,” Phyo Htet said. “We’re facing double trouble.”

Public water can only be pumped into apartment buildings when the power is on.

“Water from Gyo Phyu [one of the four reservoirs that serve water to Yangon residents] is accessible only when the electricity comes on at night. If it comes on in the daytime, it’s hopeless because many households are all trying to use it at the same time,” she added.

For some years now, at least one household member goes to bed after midnight or 1 a.m., waiting to pump up water.

Some six- or eight-story apartments dig wells and pump up groundwater for their residents, but in other buildings that may not be an option.

The limited access to water makes it difficult for Phyo Htet and her family to mitigate the effects of the heat on their health, be it by showering or making cups of tea.

Luxury commodity

In Myanmar, electricity is increasingly a luxury rather than a basic necessity—in stark contrast to more developed economies in ASEAN such as Singapore and Thailand.

In densely packed urban residential areas, power supply is also essential for fans and air conditioning, especially in the summer months that are just around the corner.

Dr. Nora, a professor teaching online at a foreign university, said she often cannot sleep because it is so hot.

Without electricity, she said, a hand fan is the only way to cool down, be it at night or during online classes.

More hotter days projected

The year 2024 has been recorded as the hottest year on record, with worldwide average temperatures exceeding the 1.5-degree Celsius target of global warming set in the UN Paris agreement from 2016, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

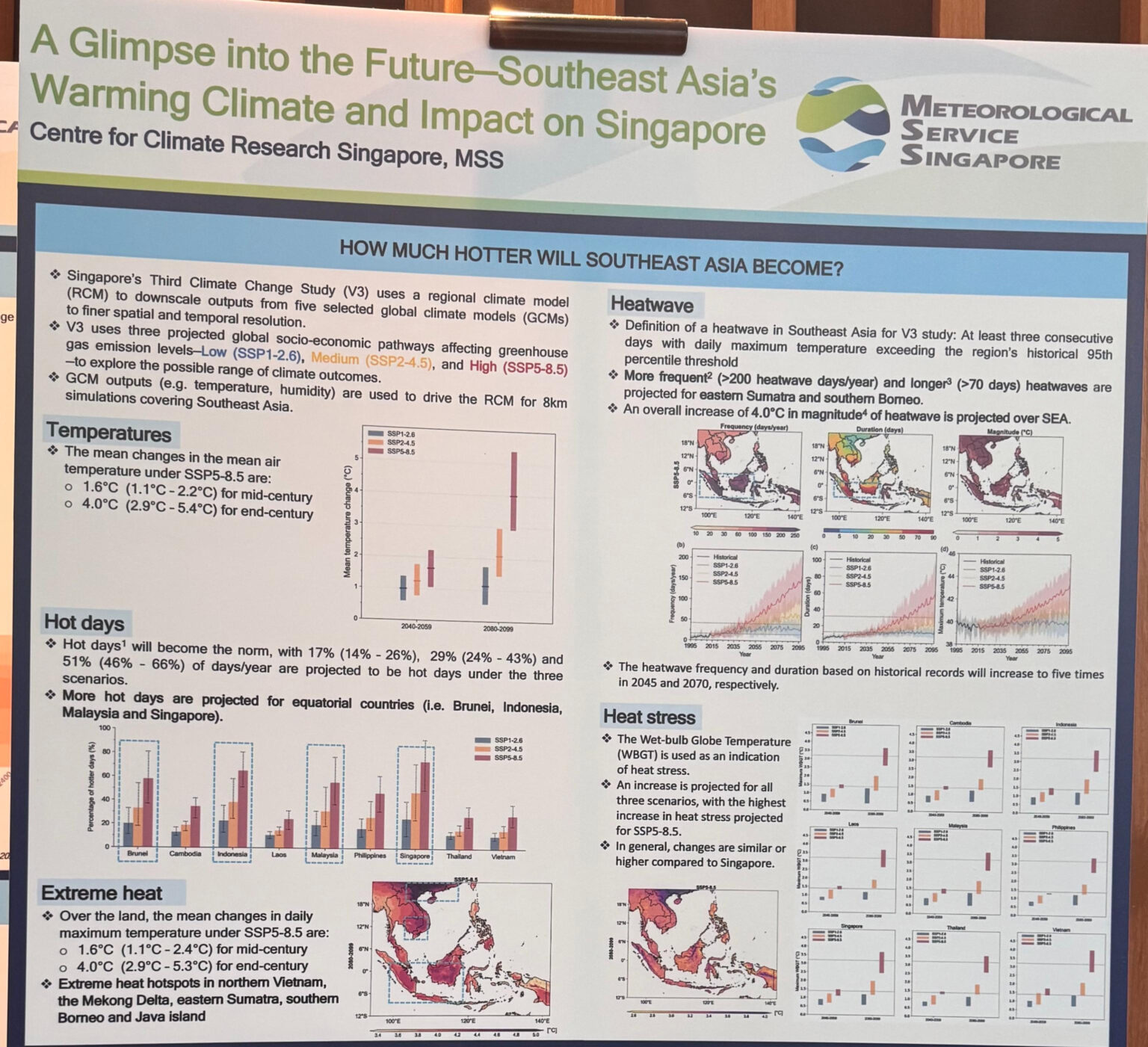

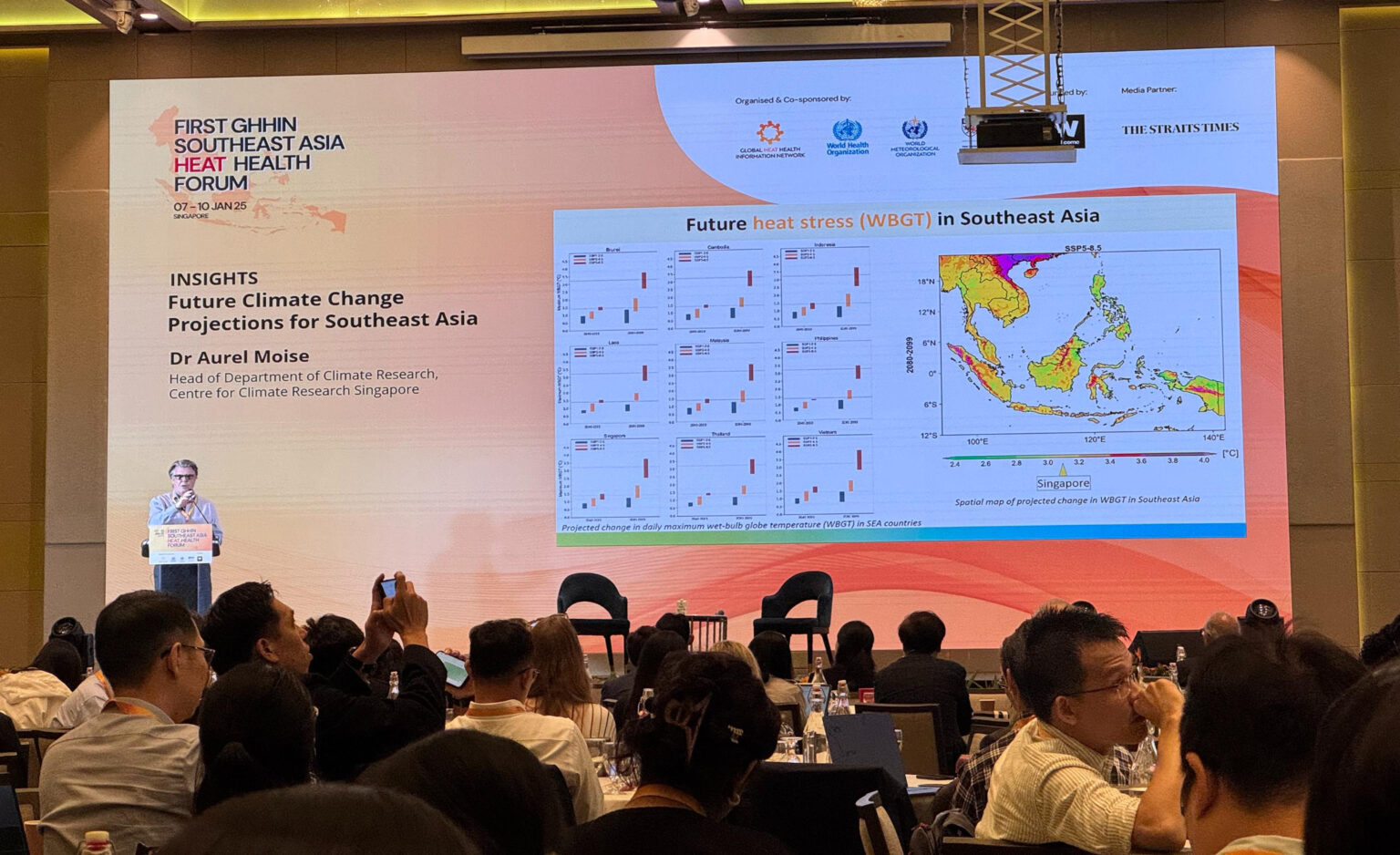

At a forum in Singapore in early January, Dr. Aurel Moise of the Center for Climate Research Singapore (CCRS) said that Southeast Asia faces more extreme rainfalls, dry spells, and daily maximum temperatures.

In April last year, Magwe Region’s Chauk recorded a temperature of 48.2 degrees Celsius, while the mercury in Yangon rose over 40 degrees.

At least 1,473 people reportedly died in Myanmar from heat-related causes that month. That was almost six times more than in 2010, when 260 heat-related deaths were recorded during the summer months, according to the Myanmar Red Cross Society (MRCS).

The MRCS also works on responses to heatwaves in the communities, including disseminating early warning messages, raising awareness, providing first aid posts, and building shaded spaces.

But support is limited, and the ongoing political crisis restricts both humanitarian assistance and awareness-raising in the communities. And of course the power outages make things worse.

Myanmar does not yet have a meteorological heat sensing system such as the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature sensor (WBGT) that measures heat stress in direct sunlight that affects humans.

Singapore has been using the WBGT monitoring system for several years so that the data can help shape policy-making for climate resilience and public awareness on staying healthy in the heat.

Slow electrification

Myanmar has been suffering electricity shortages for decades.

According to the 2019 census, just over half or 53 percent of households were connected to the national grid.

In 2018, Myanmar’s civilian National League for Democracy government laid out a plan to electrify 55 percent of the total 10.89 million households by March 2021, 75 percent by 2026, and 100 percent by 2030.

But the coup interrupted these plans and forced Myanmar to stay in the dark.

As of early January, electricity supply reached 48 percent in Yangon, 17 percent in Mandalay, and 35 percent in other regions and states including the capital Naypyitaw, according to the junta-controlled New Light of Myanmar.

Yet 10 years ago, almost 70 percent of Yangon’s households had access to electricity. Yangon is home to more than 7.36 million people, and more than 5.16 million are urban residents.

On Jan.17, the junta said electricity generation has decreased by 1,009 megawatts, with daily generation of 2,200 MW, while supply has declined to about 50 percent of total production capacity.

The junta has consistently blamed the power shortage on resistance groups that are calling for the return of civilian rule, and accused them of destroying 14 major power transmission lines from power plants.

The World Bank said in 2023 that the power crisis has worsened steadily since 2021. “Many of the challenges in power sector are structural, fundamental, and linked with political instability, conflict, and macroeconomic conditions,” it said in a report.

Quota system

Since January, households in Yangon’s townships have been provided with power on a rotating basis among three groups, each getting theoretically four hours on followed by eight hours off.

Consumers can do nothing but wait their turn, but most of the time they feel cheated as they only get two hours of electricity per day.

Where educator Zora lives, the power often comes on from 1 a.m. to 5 a.m.

On such nights she does not go to bed until 3:30 a.m. after all her power sources are charged and the water tank is full. Her sleep routine has become abnormal: some nights she goes to sleep at 9 p.m. and gets up at 1 a.m. to catch up with her energy-storing routine.

“But the power supply is not enough, and it takes a long time to fully charge my power banks,” Zora said.

On warm nights in summer, she sits absolutely still in her 15 ft. by 60 ft. apartment and waits for the time to pass to conserve her energy.

Confronting this challenge daily, Yangon residents are naturally afraid of the approaching hot season.

Phyo Htet said, “I hope for more rainy days. Once we have enough rainwater, it might help with hydropower generation and we might get access to more electricity.”

“When it’s very hot and there is no electricity we can’t sleep at all at night,” she added.

January is cool with a relatively dry northeast monsoon. Myanmar’s hottest days in March and April are yet to arrive.

All interviewees’ names have been changed to protect their identity.