Lost in the heat: The critical miscalculation in India’s heatwave mortality data

Published: April 9, 2025

India

This article was originally published by Down to Earth

Many heat-related deaths go unrecognised or are misclassified. Physicians often record only the immediate medical cause on death certificates, without acknowledging the role of heat as the underlying trigger. Such serious underestimation leads to serious misallocation of resources

Heatwaves have become India’s most dangerous disasters in terms of human mortality. Three of the five warmest years in India have been recorded in the past decade (2015-2024). Heatwaves in India are projected to occur thirty times more often by the end of the century if the global mean temperature increases by 2 degrees Celsius.

Per our estimate (see below), a single heatwave — even one lasting just a few days — causes tens of thousands of excess deaths in India. Despite the rising toll, heatwave mortality remains under-reported, poorly tracked, and largely absent as a target for preventive actions.

Discrepancies in official mortality reports

Between 2000 and 2020, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reported 20,615 heatstroke deaths, based on its annual Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India reports (NCRB, 2000-2020). During the same period, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) listed 17,767 heatwave deaths, based on state-reported disaster mortality compiled under the Annual Report on Heatwaves in India (NDMA, 2021). In contrast, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) recorded just 10,545 deaths in its Climate Hazards and Vulnerability Atlas of India, using data from State Disaster Management Authorities (IMD, 2022). These figures, all from official government sources, differ by nearly a factor of two, and the discrepancies arise from differences in methodology, data sources, and reporting responsibilities. Nevertheless, they give the impression that annual excess mortality from heatwaves in India is about 1,500, a tiny number relative to daily all-cause deaths in India of about 25,000.

Peer-reviewed studies suggest the actual death toll from heatwaves is far higher than both official and media counts. Many heat-related deaths go unrecognised or are misclassified. Public health experts note that physicians often record only the immediate medical cause on death certificates, without acknowledging the role of heat as the underlying trigger. As a result, official statistics “barely scratch the surface” of the true human cost of heatwaves.

This undercounting has led to serious inattention in terms of public health response and resource allocation. Without reliable data, there is little basis for targeting adaptation or health preparedness at the right locations. According to an estimate by Zhao et al. (PLOS Medicine 2024), India accounted for 20.74 per cent of global heatwave-related deaths between 1990 and 2019. Another study by Xu et al. (PNAS 2020) estimates that under a high-emissions scenario (RCP8.5), annual heat-related deaths in India would increase 25-fold by 2100, reaching over 1.5 million deaths per year. However, both studies provide projections at broad regional or national scales. They do not offer the district-level granularity needed for targeted policymaking, especially in a country as climatically and socioeconomically diverse as India. Neither study suggests preparatory actions in terms of either policy or infrastructure.

Heatwave mortality at the district level

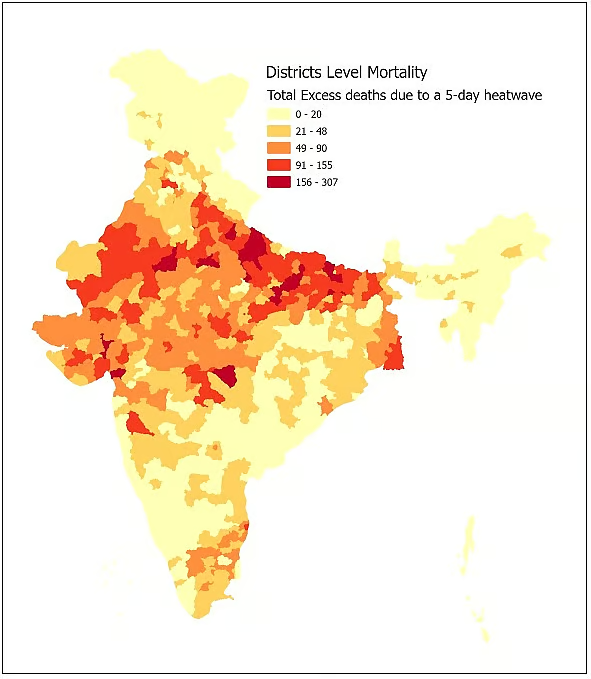

So far, the only epidemiological estimates of heatwave-attributable mortality in India come from a recent multi-city study by de Bont et al. (Env. International 2024), which analysed the short-term increase in daily mortality during heatwave events in 10 Indian cities. It showed that even a single day of extreme heat can increase mortality by 10-25 per cent, while prolonged five-day events can raise it by over 30 per cent. However, India has over 700 districts, and most of the population lives outside the limits of these 10 cities. To estimate district-level increases in mortality, we extrapolated the findings of de Bont et al. to all districts of India. We combined city-specific heat-mortality risk coefficients with district-level population and mortality data, along with district-level climate classification based on Köppen–Geiger zones. Following de Bont et al, we defined heatwaves using a percentile-based approach: any day where temperatures exceed the local 97th percentile (based on 2008-2018 data) counts as an extreme heat event. We also took into account the average altitudes of districts and their geographical location in assigning their climate profile to the most appropriate city from the 10 cities considered by de Bont et al. We assume that the incremental increase in district mortality is equal to that of the city to which the district is matched. We selected two scenarios from de Bont et al: a single-day heatwave, and a prolonged five-day heatwave.

Our analysis yields the first district-wise estimates of heatwave-induced excess mortality in India. The results are significant:

● A single day of heatwave across India leads to an estimated 3,400 excess deaths nationally.

● A single five-day heatwave leads to approximately 30,000 excess deaths, distributed across rural and urban districts.

● Assuming five heatwaves of five-day duration each summer, our analysis estimates a conservative lower bound of approximately 1,50,000 excess deaths each summer across India. This figure likely understates the true burden, as the de Bont estimates are based on data from the pre-2018 decade, and both the frequency and intensity of heatwaves are projected to significantly increase in the coming years.

● The six worst-affected districts are Ahmedabad, Jaipur, Prayagraj, Patna, Kanpur, and Lucknow — each experiencing more than 180 additional deaths during a single five-day heatwave. Among the states, Uttar Pradesh alone accounts for over 8,000 deaths per heatwave, the highest among all states, followed by Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Gujarat.

Rural districts may have higher heat-mortalities than our estimates based on the de Bont et al (2024) urban data. They have lower access to healthcare, poorer infrastructure, and their lower incomes and higher occupational exposure (e.g., outdoor labour) make a larger proportion of the population particularly vulnerable to heatwaves. In many districts, there is no local Heat Action Plan in place. Mortality risk is not just a function of temperature or humidity. It also depends on exposure duration, cumulative physiological stress, infrastructure quality, particularly for vulnerable populations — including children, older adults, pregnant women, people with pre-existing health conditions, and outdoor manual workers.

Urgent actions for this summer

The preventive measures are clear. Strong and repeated messaging for avoiding sunlight-exposure, dehydration, and hard labour during the heatwave, anticipatory action, early warning systems, and public communication can significantly reduce mortality during extreme heat events. Successful examples, such as the Ahmedabad Heat Action Plan, have demonstrated that early warnings, targeted outreach, and medical preparedness can reduce excess deaths by up to 27 per cent. These interventions need to be extended to rural districts and smaller cities that face high risk but currently lack institutional mechanisms to respond.

Specific measures include:

● Establishing public cooling shelters and shaded rest areas, especially for outdoor workers.

● Ensuring free or highly affordable access to ice slurry, oral rehydration solutions, and emergency medical care during heatwaves.

● Promoting public awareness about the risks from hyperthermia, and the benefits of hydration, and preventing core-temperature rise — for instance, correcting common bad practices such as consuming hot tea in extreme heat, which can exacerbate hyperthermia.

● Modifying working hours and school schedules, pausing outdoor sports activities during heat alerts.

● Upgrading health infrastructure to handle heat-related illnesses, especially in high-risk districts.

Extreme heat should be treated as a recurring and intensifying climate disaster, not a background risk. Heatwave preparedness and response must be integrated into disaster management and public health planning at the district level, with reliable data and accountable institutions.

The evidence is now available. The mortality burden is significant, growing, and under-acknowledged. District-level data can enable targeted action — but only if institutions recognise heatwaves as a grave public health hazard. The time to act is now; the more we delay, the more lives are lost or put at risk every summer.

Supporting information

Detailed district-level estimates and additional analysis are available in the supplementary Excel dataset provided here.

Ashok Gadgil is Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department of UC Berkeley. He is also affiliated with the India Energy and Climate Center of UC Berkeley (http://iecc.gspp.berkeley.edu)

Piyush Narang is policy researcher with the India Energy and Climate Center of UC Berkeley

Views expressed are the authors’ own and don’t necessarily reflect those of Down To Earth