Earth’s hottest recorded year was 2023, at 2.12 degrees F above the 20th-century average. This surpassed the previous record set in 2016. So far, the 10 hottest yearly average temperatures have occurred in the past decade. And, with the hottest summer and hottest single day, 2024 is on track to set yet another record.

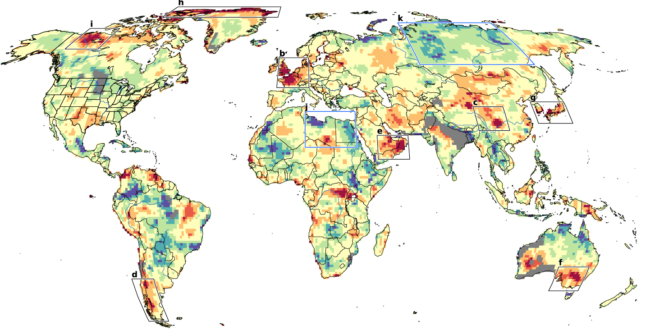

All this may not be breaking news to everyone, but amid this upward march in average temperatures, a striking new phenomenon is emerging: distinct regions are seeing repeated heat waves that are so extreme, they fall far beyond what any model of global warming can predict or explain. A new study provides the first worldwide map of such regions, which show up on every continent except Antarctica like giant, angry skin blotches. In recent years, these heat waves have killed tens of thousands of people, withered crops and forests, and sparked devastating wildfires.

“The large and unexpected margins by which recent regional-scale extremes have broken earlier records have raised questions about the degree to which climate models can provide adequate estimates of relations between global mean temperature changes and regional climate risks,” says the study.

“This is about extreme trends that are the outcome of physical interactions we might not completely understand,” said lead author Kai Kornhuber, an adjunct scientist at the Columbia Climate School’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “These regions become temporary hothouses.” Kornhuber is also a senior research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria.

The study was just published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study looks at heat waves over the past 65 years, identifying areas where extreme heat is accelerating considerably faster than more moderate temperatures. This often results in maximum temperatures that have been repeatedly broken by outsize, sometimes astonishing, amounts. For instance, a nine-day wave that hammered the U.S. Pacific Northwest and southwestern Canada in June 2021 broke daily records in some locales by 30 degrees C, or 54 F. This included the highest ever temperature recorded in Canada, 121.3 F, in Lytton, British Columbia. The town burned to the ground the next day in a wildfire driven in large part by the drying of vegetation in the extraordinary heat. In Oregon and Washington state, hundreds of people died from heat stroke and other health conditions.

These extreme heat waves have been hitting predominantly in the last five years or so, though some occurred in the early 2000s or before. The most hard-hit regions include populous central China, Japan, Korea, the Arabian peninsula, eastern Australia and scattered parts of Africa. Others include Canada’s Northwest Territories and its High Arctic islands, northern Greenland, the southern end of South America and scattered patches of Siberia. Areas of Texas and New Mexico appear on the map, though they are not at the most extreme end.

According to the report, the most intense and consistent signal comes from northwestern Europe, where sequences of heat waves contributed to some 60,000 deaths in 2022 and 47,000 deaths in 2023. These occurred across Germany, France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and other countries. Here, in recent years, the hottest days of the year are warming twice as fast the summer mean temperatures. The region is especially vulnerable in part because, unlike places like the United States, few people have air conditioning, because traditionally it was almost never needed. The outbreaks have continued. In September, new maximum temperature records were set in Austria, France, Hungary, Slovenia, Norway and Sweden. Well into October, many parts of the U.S. Southwest and California saw record temperatures for the month more typical of midsummer.

The researchers call the statistical trends “tail-widening”―that is, the anomalous occurrence of temperatures at the far upper end, or beyond, anything that would be expected with simple upward shifts in mean summer temperatures. But the phenomenon is not happening everywhere; the study shows that maximum temperatures across many other regions are actually lower than what models would predict. These include wide areas of the north-central United States and south-central Canada, interior parts of South America, much of Siberia, northern Africa and northern Australia. Heat is increasing in these regions as well, but the extremes are increasing at similar or lower speed than what changes in average would suggest.

Climbing overall temperatures make heat waves more likely in many cases, but the causes of the extreme heat outbreaks are not entirely clear. In Europe and Russia, an earlier study led by Kornhuber blamed heat waves and droughts on wobbles in the jet stream, a fast-moving river of air that continuously circles the northern hemisphere. Hemmed in by historically frigid temperatures in the far north and much warmer ones further south, the jet stream generally confines itself to a narrow band. But the Arctic is warming on average far more quickly than most other parts of the Earth, and this appears to be destabilizing the jet stream, causing it to develop so-called Rossby waves, which suck hot air from the south and park it in temperate regions that normally do not see extreme heat for days or weeks at a time.

This is only one hypothesis, and it does not seem to explain all the extremes. A study of the fatal 2021 Pacific Northwest/southwestern Canada heat wave led by Lamont-Doherty graduate student Samuel Bartusek (also a coauthor on the latest paper) identified a confluence of factors. Some seemed connected to long-term climate change, others to chance. The study identified a disruption in the jet stream similar to the Rossby waves thought to affect Europe and Russia. It also found that decades of slowly rising temperatures had been drying out regional vegetation, so that when a spell of hot weather came along, plants had fewer reserves of water to evaporate into the air, a process that helps moderate heat. A third factor: a series of smaller-scale atmospheric waves that gathered heat from the Pacific Ocean surface and transported it eastward onto land. Like Europe, few people in this region have air conditioning, because it is generally not needed, and this probably upped the death toll.

The heat wave “was so extreme, it’s tempting to apply the label of a ‘black swan’ event, one that can’t be predicted,” said Bartusek. “But there’s a boundary between the totally unpredictable, the plausible and the totally expected that’s hard to categorize. I would call this more of a grey swan.”

While the wealthy United States is better prepared than many other places, excessive heat nevertheless kills more people than all other weather-related causes combined, including hurricanes, tornadoes and floods. According to a study out this past August, the yearly death rate has more than doubled since 1999, with 2,325 heat-related deaths in 2023. This has recently led to calls for heat waves to be named, similar to hurricanes, in order to heighten public awareness and motivate governments to prepare.

“Due to their unprecedented nature, these heat waves are usually linked to very severe health impacts, and can be disastrous for agriculture, vegetation and infrastructure,” said Kornhuber. “We’re not built for them, and we might not be able to adapt fast enough.”

The study was also coauthored by Richard Seager and Mingfang Ting of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and H.J. Schellnhuber of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.