Occupational heat stress can impact the productivity, safety and health of both outdoor and indoor workers who don’t have access to appropriate cooling.

- Heat stress can affect worker safety and health at considerably lower temperatures than for inactive people.

- Heat stress impacts productivity and sectoral economies – especially in highly heat vulnerable regions.

- For workers and businesses to be able to cope with heat stress, appropriate policies, technological investments and behavioural change are required.

- Responses to heat stress in both indoor and outdoor sectors should include technological improvements, skills development, awareness raising and employment standards.

Every year, 22.85 million occupational injuries, 18,970 work-related deaths, and 2.09 million DALYs attributable to excessive heat

Occupational heat stress is created by the combination of the environment and working conditions. Temperatures above 24-26°C are associated with reduced labour productivity. At 33-34°C, a worker operating at moderate work intensity loses 50% of his or her work capacity, while exposure to excessive heat levels can lead to heat stroke and death.

By 2030 the equivalent of more than 2% of total working hours worldwide is projected to be lost every year, either because it is too hot to work or because workers have to work at a slower pace – a productivity loss equivalent to 80 million full-time jobs. In Southern Asia and Western Africa the resulting productivity loss may even reach 5%. Tool tip Working on a warmer planet: The impact of heat stress on labour productivity and decent work

Impacted Sectors

Workers in many sectors are affected, but certain occupations are especially at risk because they involve more physical effort and/or take place outdoors. Such jobs are typically found in agriculture, natural resource management, construction, refuse collection, emergency repair work, transport, outdoor and street vending, tourism and sports.

Industrial workers in indoor settings are also at risk if temperature levels inside factories and workshops are not regulated properly. At high heat levels, performing even basic office and desk tasks becomes difficult as mental fatigue, and physiological and cognitive decline sets in due to heat strain. Source Working on a Warmer Planet (ILO)

The agricultural sector alone accounted for 83% of global working hours lost to heat stress in 1995 and is projected to account for 60% of such loss in 2030. Whereas construction accounted for just 6% of global working hours lost to heat stress in 1995, this share is expected to increase to 19 % by 2030. Significantly, most of the working hours lost to heat stress in North America, Western Europe, Northern and Southern Europe and in the Arab States are concentrated in the construction sector. Source Working on a Warmer Planet (ILO)

Vulnerability

Some groups of workers are more vulnerable than others because they suffer the effects of heat stress at lower temperatures. Older workers, in particular, have lower physiological resistance to high levels of heat. Yet they represent an increasing share of workers – a natural consequence of an ageing population. Source Working on a Warmer Planet (ILO)

Workers in tropical and subtropical subregions are at higher risk of heat stress because of a combination of both extreme temperatures and the high share of agriculture in total employment, a sector particularly exposed to heat stress. These are densely populated geographical areas characterized by high rates of informality and vulnerable employment, making workers particularly susceptible to rising temperatures. Source Working on a Warmer Planet (ILO)

Management and Adaptation Solutions

Governments, Employers and Workers

Governments must work together with workers’ and employers’ organizations to design, implement and monitor mitigation and adaptation policies, as recommended in the ILO’s 2015 Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all. Social dialogue plays a crucial role in the development of national policies, including policies on occupational safety and health. With the help of social dialogue tools, such as collective agreements, employers and workers can design and implement policies for dealing with heat stress that are tailored to the specific needs and realities of their workplace.

Employers’ and Workers’ Organizations

Although governments are instrumental in creating a regulatory and institutional environment that facilitates behavioural change at the workplace level, the role of both employers’ and workers’ organizations is no less crucial to a successful implementation of adaptation measures.

In addition to the enforcement of occupational safety and health standards, appropriate measures are necessary to improve early warning systems for heat events and to ensure that social protection covers the entire population. International labour standards, such as the Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155), can help to guide governments when designing national policies to tackle the occupational safety and health hazards associated with heat stress. Source Working on a Warmer Planet (ILO) Another important resource for employer and worker organizations is The Scientific Committee on Thermal Factors (SCTF) of the International Commission on Occupational Health – an active research and analysis network working for the protection of working people from excessive heat and cold exposures.

Sectoral Response: Agriculture

The long-term options for reducing the impact of heat stress on agriculture include promoting mechanization and skills development in order to ensure higher productivity and food security. Measures for monitoring and raising awareness of local weather conditions can help rural households to adapt to heat stress conditions. Source Working on a Warmer Planet (ILO)

Sectoral Response: Construction

As for the construction sector, smart urban planning could help significantly to mitigate heat stress on construction sites in large cities in the medium and long term. Moreover, specific measures for the monitoring of on-site weather conditions, enhanced information sharing and communication, and technological improvements can enable construction workers and their employers to adapt more effectively to heat stress. Source Working on a Warmer Planet (ILO)

Personal Cooling, Heat Illness Detection and Management

Management and adaptation to extreme heat at work requires an awareness of the signs and symptoms of heat-related illness, and an understanding of the measures that can be taken to immediately reduce core temperature. Avoidance of thermal risk and early recognition of cold or heat stress are the cornerstones of preventive therapy. Source Thermoregulatory disorders and illness related to heat and cold stress

Workers should be trained to recognize and address the early signs of heat illness. Workers should be aware of and have access to personal cooling actions such as cool, shaded areas for breaks, clean drinking water, and breathable clothing suitable for local temperatures. Tool tip Learn more about managing and adapting to extreme heat impact on the body here.

Key Resources

Report

International Labour Organization (ILO)

2024

Research

Publication

Research

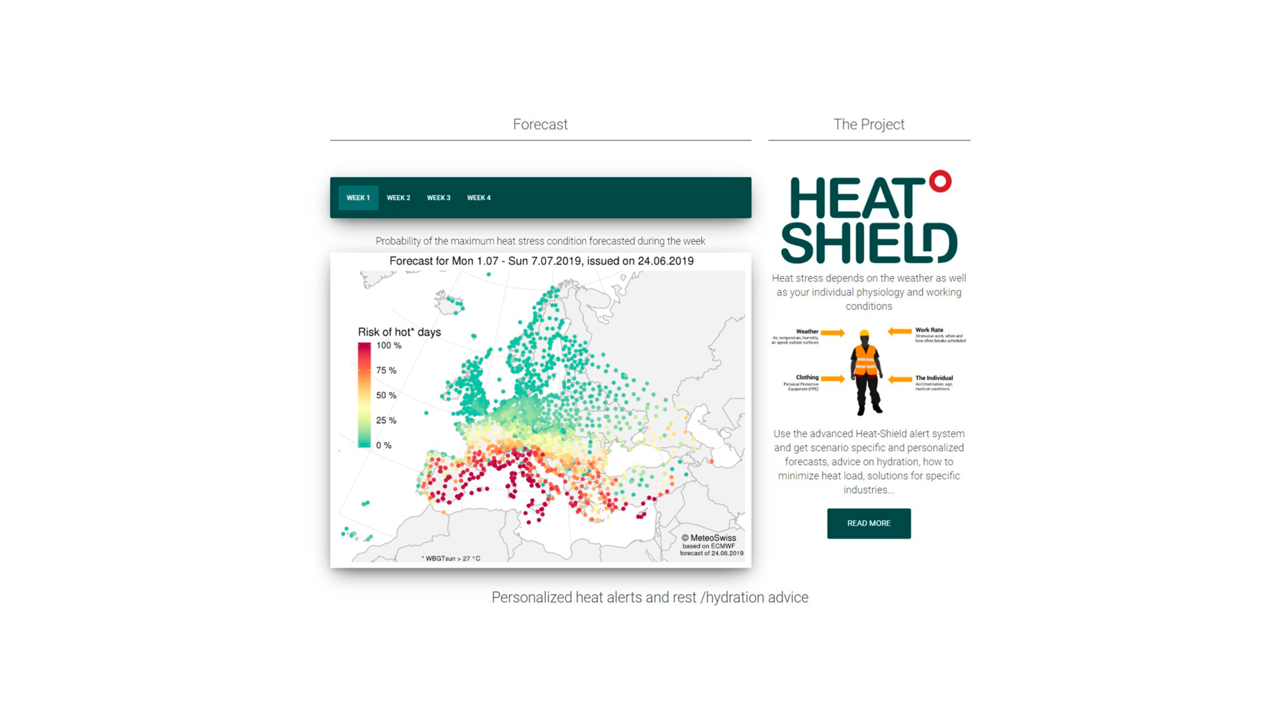

Mobile App

Guidance

Workplace Health and Safety Council

2020

Research

Guidelines

Ministry of Manpower (MOM) Singapore

2024

Learn more

For information on personal cooling and heat illness detection and management, please see our section on managing and adapting to heat in the body.

Page Contributors

Jason Lee, Lars Nybo, Nicola Gerrett, Andreas Flouris